African art: a growing market

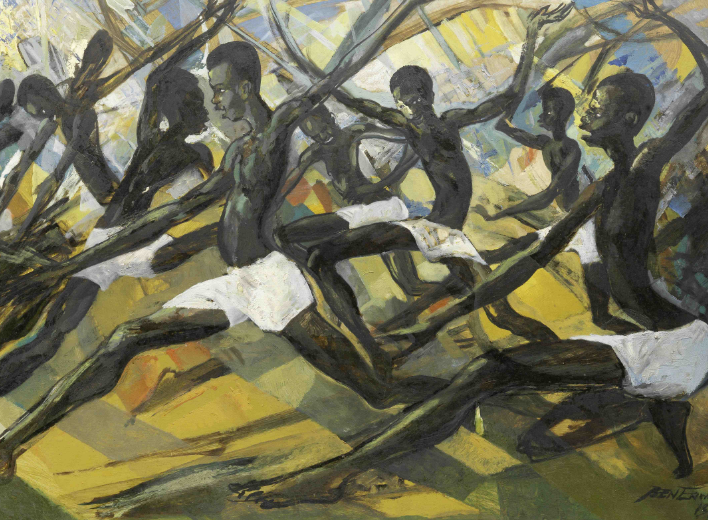

Last month’s highly successful auction of Contemporary African art at Bonham’s in London is one of several indicators that African art is becoming increasingly attractive to collectors.

The success of the event is a far cry from the early days of Bonham’s African sales, which were started by Giles Peppiatt, director of African Art at Bonham’s, six years ago.

“When we first started these sales it was quite tricky – we were the first to really have sales of contemporary African art and the interest was muted to say the least,” he says.

“Over the past six years things have changed dramatically and over the past three sales we have been incredibly busy with collectors, media enquiries, institutions, museums – the full range really. This is because Africa in general and African art in particular seems to have become a much more interesting subject.”

He says that the interest is being driven in part by the ongoing search for the ‘next big thing’, but it also reflects the quality of art coming out of Africa.

“For a long time Africa has been this sleeping giant; now it is waking and people are taking notice of its art,” he says. “I think a lot of people regard it as a market that potentially is going to be very hot and they want to get in at the ground level.

“The other factor is that the art that’s coming out of Africa is amazing – the market is very strong and there is some wonderful being produced.”

It’s not just the contemporary art that is causing excitement; there is considerable demand for older pieces too.

London art dealer Bryan Reeves traces the European appetite for African art back to the early part of the last century, when it first began to appear on the streets of Paris. At that time a Colonialist view of Africa led to African art being dubbed ‘primitive’, but gradually the Western world awoke to the wealth and diversity of Africa’s art.

In the 1960s the supply of original artworks started to dry up and the pieces that are now regarded as masterpieces started to be perceived as limited and rare. London drove the development of an African art market in Europe and at the top end, pieces started to fetch tens of thousands of pounds.

Where dealers specialising in African art had been few and far between, collectors now worked with dealers and galleries became well established in London, Paris, New York and Brussels. Reeves says that these players successfully redefined the African art market, reaching out to the broader ‘fine art’ market by dropping the ‘tribal art’ label and adopting the simple term ‘African art.’

There has been a corresponding expansion of the field of collectors, with more young people entering the market. He notes that these buyers are keen to buy pieces of genuine quality, but that distinguishing pieces of low value that have been made for the tourist trade from genuine collectors’ items is a challenge in this field.

“For the person who is not used to feeling and touching it, it can be very hard to tell,” he says. “It helps to have an opinion from a dealer.”

London-based dealer Michael Backman agrees that with African art, and more broadly, tribal art, authenticity and provenance are key:

“It can be a good investment if you know what you are doing, but the vast majority of tribal items on the market are reproduction, souvenir or fake pieces, and these have little or no investment potential,” he says. “Get it right and you might be able to do very well. As always, the best ingredient for a sound investment is research.

“True collectors now are so suspicious of fakes that they will err on the side of caution and simply avoid anything that doesn’t scream age. The two ‘Ps’ must be observed at all times – provenance and patina.”

He adds that anxiety about fakes and reproductions has restrained the lower end of the market.

“The appetite for high-end African art has sky-rocketed. This has been due largely to the entry to the marketplace of several very wealthy collectors, including interest from Qatar. The market for lower-end African art has not kept up largely because the confidence in such pieces has been under-mined by the prevalence of reproduction and fake pieces.”

While Backman notes considerable interest from Qatar, Peppiatt observes that when it comes to Contemporary African art, the institutional sector, notably the Smithsonian and the Tate, have been very active, as have some very well-known private collectors such as Jean Pigozzi, who has exhibited his collection worldwide, and Jochen Zeitz, who is planning a museum of modern African art in Capetown.

“There is also a whole slew of people who are active but not so public – we have collectors from across Africa and across the world,” he adds.

Backman believes that African buyers will soon swell the market further: “African buyers have yet to emerge in any serious way. But that will come. First, it will be the expatriate Africans who will drive the market and then it will be the newly wealthy in Africa itself,” he says.

In Peppiatt’s view the strongest areas for African art are Ghana and Nigeria. He notes that renowned African artists El Anatsui and Ablade Glover are Ghanaian, while 30-40% of the lots in the recent Contemporary African Art sale at Bonham’s originate from Nigeria.

“Nigeria is the economic powerhouse in Africa and one can’t ignore that – both artistically and in financial terms,” he says.

For the newcomer to African art, Peppiatt’s tip is to avoid buying anything on the way to the airport.

“In order for the art you’re buying to be credible and produced by someone who is doing it for artistic reasons rather than just to sell to tourists, you’ve got to go to a reputable gallery,” he says.

While interest in African art is hotting up, there are still some artists worth snapping up early. He particularly notes El Anatsui’s, whose early work, which he believes is grossly undervalued, selling for in the region of £25,000-£28,000 while his recent big hangings can fetch as much as £500,000.

“I do think that gap will close,” he adds.

When it comes to tribal African art, Backman warns that there are few – if any – true ‘bargains’ to be had, and that in order to end up buying a fake or poor quality tourist souvenir you need to do your research.

“Go to museums and look at what they have and go repeatedly because each time you go and look at the same items you will notice something different,” he says. “Befriend a good dealer who can tell you what to look for. Avoid items that have recently come from Africa or other tribal art areas; if the items have come recently then they will most likely be reproduction pieces.”

Instead, he strongly advises looking for pieces that have been in Western collections for many decades.

“Avoid items that smell smoky – fakers often smoke their items to give them the yellowed look of age. Avoid items that are excessively ‘cute’ or whimsical – often that is a sign that the item has been made for Western eyes. Avoid items that seem to be a bargain. There are few bargains when it comes to serious artworks.”